Zhenzhilova Anastasia Grigorievna – a native of the city of Kemerovo, a veteran of the Great Patriotic War, a participant in hostilities, a participant in the Kremenchug underground in 1943. Before the war, she worked as a master of industrial training at the Kemerovo vocational school.

At the end of 1941, she wrote a statement with a request to send her to the front as a volunteer. In March 1942, the formation of the 303rd Infantry Division was completed in Kuzbass. All medical units were composed almost exclusively of women. Anastasia Grigorievna was enrolled as a medical instructor in a field mounted reconnaissance platoon, therefore, in addition to studying weapons, the ability to crawl on her bellies, she also had to learn to ride a horse.

In July 1942, the division was sent to the front, where A. Zhenzhilova received her “baptism of fire”. At the end of September, the foreman of the sanitary company was killed, and Zhenzhilova was recalled from the reconnaissance, and she was appointed the foreman of the sanrota of the 845th rifle regiment. She met the end of the war in the capital of Czechoslovakia – Prague. On May 12, 1945, the unit where A.G. Zhenzhilova served reached Berlin. On the wall of the Reichstag, Anastasia wrote: “From Kemerovo to Berlin.” She was in Kremenchug from March to September 1943. Memoirs were written in the mid-1970s.

… At the beginning of 1943, our troops went on the offensive. In the Lyubotin area, our division faced strong enemy resistance: the Nazis managed to bring up fresh tank units, and now we had to fight back. On March 8, 1943, I received new uniforms and additional rations for my platoon. I wanted to please the girls, but failed. In the afternoon, the Germans pushed our units back, we had to retreat. The head of the sanitary service ordered to hide the uniforms in the basement, they say, we’ll be back in a couple of days. But the retreat dragged on, the spring weather did not allow the troops to move quickly. Our division was surrounded. I don’t know how, but in the confusion, a 76mm cannon ran over my leg. The leg was very swollen and it became difficult to walk. At dawn, indiscriminate shooting began, and I was wounded in the injured leg.

I fell behind the infantry. I heard the rumble of tanks behind me and decided that they were ours. Well, I think that’s good, they’ll take me. A wedge heel drove up. I look, and there is a swastika on it! The Germans jumped off the wedge, tore off my cap, unscrewed the asterisk and, pushing with their rifle butts, put me on the armor – there were already several of our wounded soldiers.

We were locked in a barn. At dawn, a tarpaulin-covered truck drove up. Those who could not get into the car were dragged back to the barn, then we heard shots …

They drove us for a long time, without stopping. Finally the car stopped, we were unloaded and lined up. A German officer was standing in front of the line. In pure Russian, he

informed about the order in the concentration camp: first, run away and don’t try, you won’t get out of here; secondly, the order in the camp is strict, for the slightest violation – execution. “And now, a step forward, those who surrendered voluntarily, they have different conditions of stay,” declared the German.

The people stood in silence.

- Well, sit hungry for three days – there will be volunteers, – the officer smiled maliciously.

A command sounded, and they began to take us to the barracks. A middle-aged prisoner approached me, looking like a Georgian. - What, my dear, got caught? – He asked. – I see you have something with your leg. Try not to limp.

But I could not help limping, the pain was unbearable. Then two prisoners of war approached, at a sign from the Georgian they put me on a stretcher and carried me somewhere – like

it turned out to be in the bathhouse. There they were ordered to undress, doused with ice-cold water and carried to the dressing room. A Georgian appeared and said: “Call me a doctor. He examined my leg, said that there was nothing terrible, the injury was minor, everything would soon be over, and that we were in Kremenchuk.

Two days later, another group of prisoners of war was brought. There were two women there – my compatriot from Kemerovo, lieutenant of the medical service of our 303rd division Katya Solovyanova and junior lieutenant Lida Medvedeva from a tank brigade, a native of Primorye. I immediately became friends with Lida.

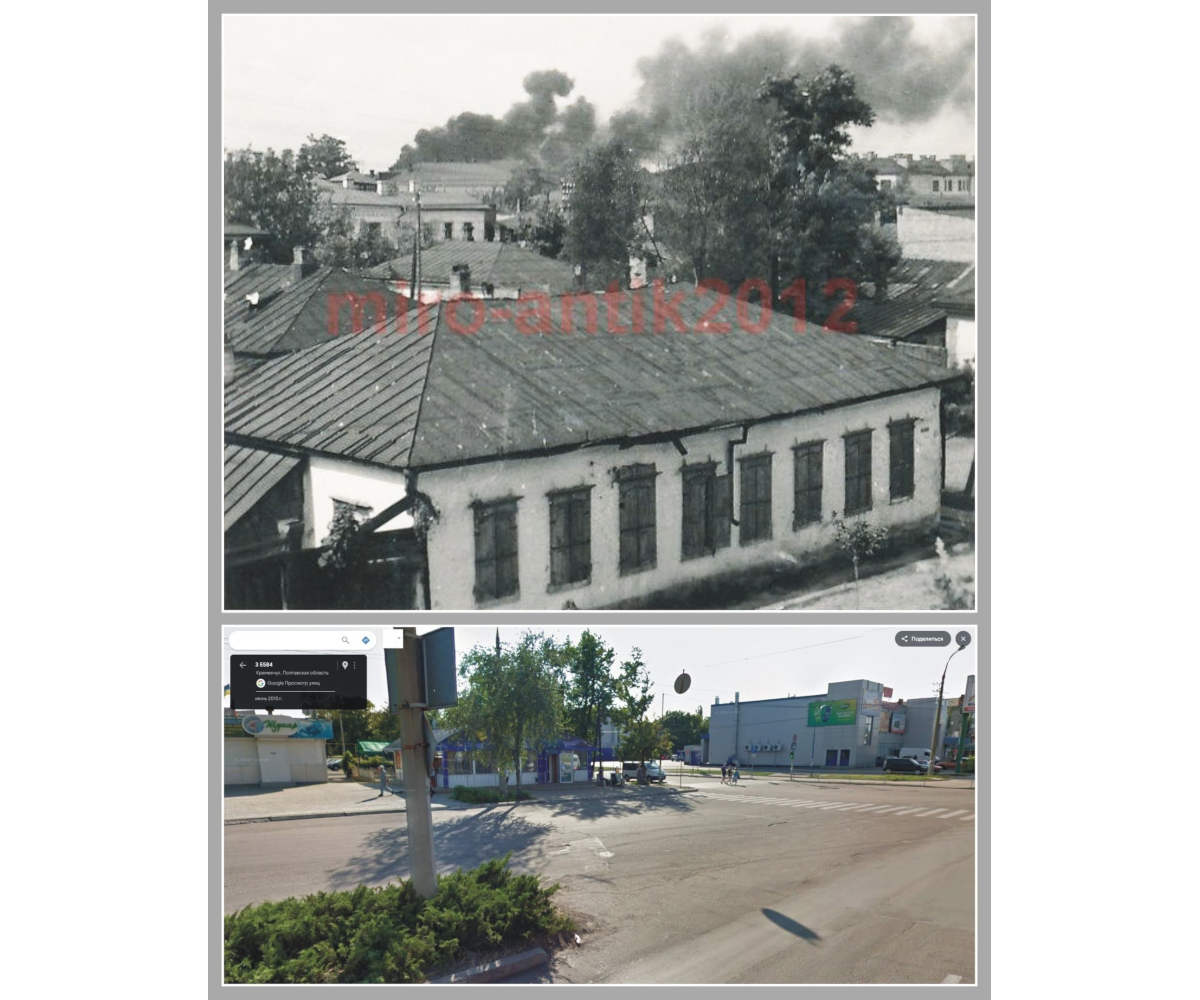

The concentration camp in Kremenchuk (the Germans called it “Stalag”) was fenced in three rows with barbed wire, and submachine gunners were stationed every 50 meters.

We were deprived of freedom, elementary human rights, but they could not kill the faith in victory. From what sources some of the prisoners of war learned about the situation at the front. And the Germans betrayed themselves by their behaviour. If the Nazis were successful in some sectors of the front, then the sentries walked around merry, started playing the harmonicas and even prepared more or less tolerable food for us. If the Nazis were defeated at the fronts, the guards walked around the camp in silence, angry, gloomy, beat the prisoners for no reason. Pits were dug outside the camp, where at dawn special brigades from the policemen took out the mutilated corpses of prisoners of war. Sometimes there was a groan, “I am still alive,” and the traitorous policemen answered: “Nothing, you will die there.”

In June – July 1943, prisoners of war were taken to work every day – they loaded wagons that were sent to the west. We understood that the front was approaching.

Doctor-gruzin Lezhava told me: “The camp will be evacuated, and you women are an extra burden. You may be shot. We will try to send you to the city hospital, they will help you escape. I need to get you an operation for appendicitis. I will only cut the upper fabrics and apply the stitches. “ - I agreed. But when I was already lying on the table in the operating room equipped for the operation, a German doctor came in and said: “Operate with me.” This is how they performed a real operation without anesthesia. Then they operated on Lida Medvedeva – they made cuts on her shoulder, where two bullets were stuck.

- After the operation, Lida and I were transported to a civilian hospital under the supervision of the local police.

- The city hospital of Kremenchuk had its own underground organization. We kept in touch with Ivan Semenovich Rudin, a career officer in the Black Sea Fleet. The city hospital was a kind of headquarters for the fight against the fascists, and we tried in every possible way to help in this struggle: we wrote leaflets, told the sick and their families about the situation at the fronts, about the inevitable victory of our army.

- In the tuberculosis department, which the Germans feared, prisoners of war, underground workers and even partisan intelligence officers often hid.

- I was recovering after the operation, and Lida Medvedeva and I were preparing an escape to the partisans. But the unexpected happened. On August 2, five fascists in black uniform entered our small ward. They were the Gestapo. I asked permission to go to the toilet, two fascists went with me. Fortunately, the toilet window was open, I got out through it and ran. Let them, I think, be shot than to suffer in the dungeons of the Gestapo. And Lida was captured. Subsequently, I received two small notes from her. In one she asked to inform her parents about her fate, and in the other, it was like this: “Dear Tasya, I am very glad that you managed to escape. The Germans decided that we were very important scouts. It is so hard for me to endure torture, I have no strength anymore. Except R. (Rudin – A.G.) he does not establish contact with anyone. There are general arrests in the hospital, they say that who has betrayed us. Goodbye. Lida.

- I was hiding in the family of Pavel Danilovich and Ekaterina Vlasyevna Shelest, who lived on the street. Chapaeva, 11. Their daughter Valentina Pavlovna also lived in this house.

- Radchenko with two sons – Yura and Vadim, were 10 and 12 years old. This family, not fearing that they could all be shot, provided assistance to the fugitive prisoners of war: they were fed, changed clothes, and provided shelter.

- Once I was sitting in the cellar (the lid was pushed aside) and rereading the notes from Lida.

- In the evening, who entered the yard.

- Today and tomorrow there will be raids. Your prisoners of war will certainly be found, – I heard a young voice. – She can’t stay here. You know that you are threatened with execution.

My hosts tried to convince the young man that they were not hiding anyone, but the unknown was persistent. He walked quickly into the cellar. There was nothing to do, and I got out. Almost immediately I felt bad: after all, I spent ten days in a dark cellar, and before that – in a dark closet of a grocery store, where Valentina Pavlovna Radchenko was a salesman.

Fortunately for us, the young man turned out to be an underground worker. At dusk, he led me to the outskirts of Kremenchug, where several dozen people had already gathered. We walked out of town one by one. Everyone carried a weapon. It fell to me to carry the disassembled rifle. We walked in the dark, and at dawn we hid in some deserted farm. The next day we reached the place where the Psel river flowed into the Dnieper. In the reeds we were met by a large group of members of the Kremenchug underground.

Familiar everyday life began for me. We went on reconnaissance, mapped the location of firing points and enemy manpower.

When units of the Soviet Army approached Kremenchug, we gave them accurate information about the Nazis.

On September 29, 1943, our troops liberated Kremenchuk. Many members of the underground joined the army. I became a medical instructor again.

Author: Gayshinska A.P.

Materials of the scientific – practical conference “Kremenchug – 435 years”