The first day of the war is June 22, 1941. Sunday. the day was sunny and warm. They heard about the beginning of the war in Yatsynivka from the loudspeakers on the radio installed in the elevator. At about 10 am, people gathered at the village council, many young people, Komsomol members. Their mood was fighting. They talked about voluntary enrollment in the Army, considered Komsomol tickets, then they hid them, carefully fastening their pockets – they took care of them.

From the first days of the war, Raisa, a teacher at the Krivushan seven-year school, volunteered for the army (I don’t remember her middle name or last name), who was a medical instructor in an anti-aircraft artillery battery. The combat position of this battery was on the floodplains, next to the dam, opposite Shcherbakivka. Her student Yakov Fedorovich Galayda also volunteered for the same battery. The battery more than once fired at fascist planes, and we, the boys, ran to watch how the battery was fighting. It was interesting to observe how the shell explosions were almost next to the plane, but there were no direct hits. Then it became known to me that the probability of hitting from anti-aircraft guns at that time was 2%.

Yakov Fedorovich Galayda came in 1947, or in 1948. His chest was decorated with medals and orders. We then already conscripts looked at them with interest. As he himself said, his combat path was from Kremenchuk, through Kobelyaki, Chuguev, the Moscow region, and later Ternopil, where he was shell-shocked. He ended the war in Austria. After Kobelyak did not see the teacher Raisa again, her further fate is unknown.

In the first days of the war, there was a lot of activity a month after the start of the war. At first, the raids were only at night, but as the front approached, they began day and night, and repeatedly.

On the Dnieper and in the backwater, a lot of boats with different cargoes have accumulated. After the first air raids and bombings, the crews of barges and steamers went ashore. The barges were mostly wooden, it was necessary to pump out water from them daily, which in the circumstances was impossible to do and they began to sink. Many villagers, even in those dangerous conditions, managed to take cargo from barges – flour, salt, kerosene. Opposite Loboykovka there was a 50-meter-long tanker barge with kerosene, which was set on fire either by aviation or by the crew. The barge burned for 1.5-2 months, burned out when the Nazis had already captured the village.

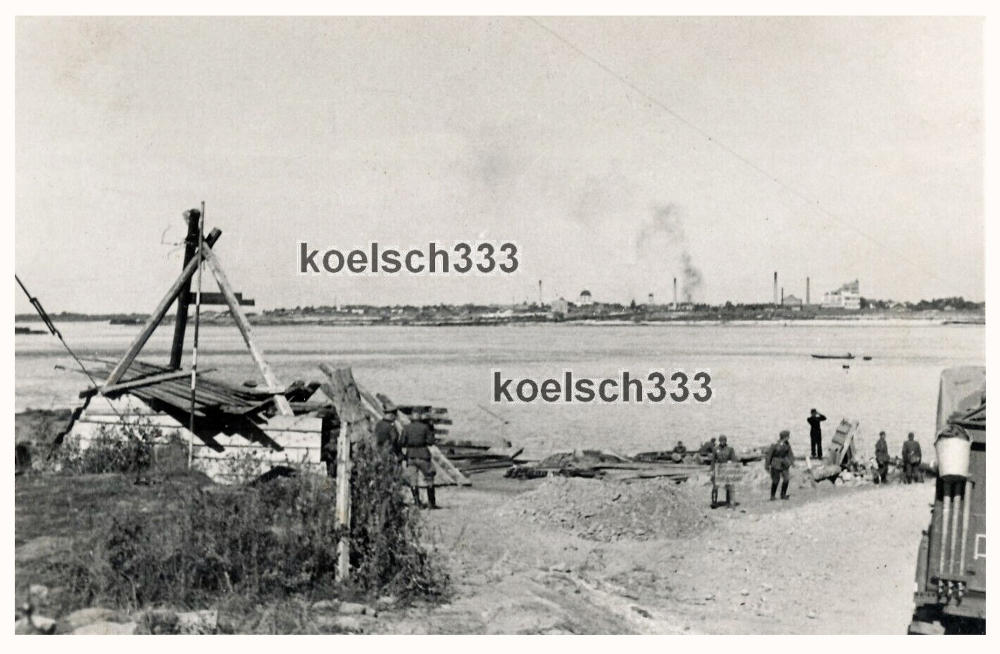

When the Germans rushed to the Dnieper, a division of the people’s militia was formed in Kremenchuk to reinforce the defending units, consisting of 3 regiments. The division took up defensive positions beyond the Dnieper, in the area of Deevskaya Gora and the forest, covering the approaches to the city of Kryukov (now the Kryukov district of the city of Kremenchuk, its right-bank part), where the Nazis rushed to capture the bridge across the Dnieper. The division repulsed the offensive of the advanced units of the Nazi troops and delayed their offensive for several days. But with the approach of the main enemy forces, when aviation and artillery strikes hit it with new force, the division at the Burty-Pavlysh line suffered significant losses and, according to the stories of the participants in the battle, the remnants retreated to the left bank of the Dnieper. The Nazis bombed the bridge, and the retreating had to cross in boats, on improvised means, or even by swimming. It should be noted that the division was mainly staffed by workers and employees of the Kryukov Carriage Building Plant, other enterprises and institutions of the city, young people (pre-conscripts) – yesterday’s high school graduates, many of whom learned how to handle a rifle in just a few days. And the soldiers of the division were armed with rifles and bottles of combustible mixture. Rifles were missing. As one of the participants in this battle, Ivan Andreevich Galayda, said, there was one rifle for 3 people. The division was poorly armed and poorly trained. Many of her soldiers fell on the battlefield. From Krivushy died on Deevskaya mountain:

Alexey Koval,

Ivan Spiridonovich Thread (“Gray”) and others.

In those troubled days, there were rumours that the Germans had landed on Deevskaya Gora beyond the Dnieper and that a militia division had allegedly been sent to destroy it. But then it turned out that these were the advanced units of the advancing German troops and the militias were not a serious force for them.

The defeat of the militias was very hard for the population. Many old men, having figured it out, later assessed that battle as a hat-throwing one, doomed to defeat in advance. Uncle Ivan, my mother’s brother Ivan Nikolaevich Koval, whose son Aleksey died on Deevskaya Hill, was especially well versed. The uncle then went to the mountain, hoping to find the grave of his son, to find out something connected with him, but he did not find anything. Since the dead were buried by local residents in mass graves, no one identified the dead. It was still warm, the corpses began to decompose, and many militiamen who died in battle were buried right at the place of death. So told the local residents of Kryukov in December 1941.

Almost until the end of August 1941, Kremenchuk enterprises and the population were evacuated to the east. Along the Dnieper, the inhabitants of Kremenchuk carried out trench work. They dug anti-tank ditches and scarps from Kurgan (from Loboykovka) to Samusievka. On the floodplains, transhei and located MZP (inconspicuous obstacles). The Nazis bypassed this line. In the deep autumn of 1941, when the Germans were already in Kremenchuk and Krivushy, a group of German senior officers were walking near the Dnieper. One of the riders flew into the MPZ. The horse fell, huddled in the wire, and the rider also flew out of the saddle and got confused. Then the German and the horse were dragged out for a long time. We watched all this from the trench and were very glad that at least this obstacle punished the Germans. Before that, these Germans came to the shelugi on the floodplains to hunt, for hares, they killed about 15 pieces. They attracted us, shepherds, to drive hares. We ran for half a day, but they did not give us anything, but we hoped. They asked for a cigar, but they didn’t give it. They showed with their hands and said: “Klein” (small).

With the release of the Nazi troops to the Kryukov-Krylov line (August 9, 1941, the Nazis captured Kryukov), the enemy began to constantly shell Kremenchuk and nearby villages with artillery, and air raids became more frequent. I remember how once German aircraft bombed the backwater from lunch to evening. Planes approached in groups and dropped bombs. Fascist pilots practised bombing with impunity. Several bombs hit nearby huts, and one or two families were killed. the broken barges sank, but the backwater was not deep, and most of the barges were in a semi-submerged state. Then some cargoes were taken out of them with hooks. One barge was with soy cutlets in tomato, and glass jars of 0.5 litres. We went with my father when the Nazis occupied the village and the city, and we managed to pull out two boxes with a hook.

During the period when the Nazis took up positions on the right bank of the Dnieper, the troops of the Red Army were almost invisible. Those small units that occupied defensive positions in the Krivushy region were poorly, if not supplied with food at all. the population and the collective farm provided them with food assistance. In the village, 3 or 4 positions were equipped, in which they defended about an infantry platoon without artillery. There was an artillery battery of 122 mm horse-drawn howitzers, which arrived 1.5-2 weeks before the Germans captured the village, which had already been in battle somewhere earlier. Due to the lack of ammunition, or for some other reason, the battery was in the yard of the collective farm brigade on Gorislavka, where the Nazis captured it. True, the guns were dismantled, the gun locks were removed, and, retreating, the battery personnel stole horses. Then the Germans dragged away with their tailless heavy horses somewhere in the city.

Anticipating the advance of the Nazis on the city and fulfilling the directive of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR on June 29, 1941, on the destruction of all valuable property during the retreat so that the enemy would not get it, the city authorities began to destroy and burn everything that could not be evacuated, all objects military and strategic importance. The elevator burned warehouses, a confectionery factory, other plants and factories, and shops. On the Dnieper, in the backwater, barges were burning. But the enemy did not advance. Local authorities and their actions were not observed. In this situation, in some areas of the city, they began to take away shops, and disassemble the property of burning and unguarded objects. Mostly people sorted out food, but there were many who dragged everything that was more valuable. Our father forbade us to bring home anything other than food. He said that not a single government during the years of the Civil War shot for food. We wheelbarrow carried a sack of flour from a sunken barge on the Dnieper, took kerosene from a burning barge, and grain from an elevator.

I remember how on the burning elevator crowds of people, on foot and with horses, were dragging what they could. Probably the Germans saw this because of the Dnieper and began shelling. The shells exploded, but not all people ran away. They hid, waited until the shelling was over and got back to work. As far as I remember no one was hurt. The collective farm leadership remained in place and sent carts for property, and some equipment from the burning facilities.

I remember how the townspeople scooped up molasses with buckets in the yard of the confectionery factory. A warehouse with wooden barrels of molasses was on fire. We also brought a bucket or two of molasses. You would pour this molasses into a plate with coals from a barrel, large pieces of coals were thrown away, and small ones went with molasses and bread for a sweet soul. Then they regretted that they took so little.

Somewhere at the end of August 1941. , during the period of anarchy, in the evening, the PO-2 aircraft began to fly over the village. Circled, flew low, circled again. They thought that it was German and opened fire from a small arms fighters of the Red Army unit defending the village, which occupied positions on the kuchugurs. After the shelling, the plane did not circle anymore, but landed on an oat field on Zarudya, opposite the village club. The pilot said that he had flown for some kind of railway chief, but he did not know where to look for him. I wanted to sit down, but I was afraid that the village was occupied by the Germans, and after the shelling, I was convinced that there was no enemy and sat down. the next day they found that boss and the plane flew away.

At the end of August 1941 the collective farm herd – cows, young and working cattle – was stolen from the village to the east. The evacuation was led by farm manager Vasily Trofimovich Yatsyna. But in the village, there were many cattle evacuated from the Dnieper, which roamed the fields and pastures. Stray cows. due to the fact that they stopped milking – they got sick. In addition, they spread the disease of livestock – foot and mouth disease.

Somewhere at the end of November 1941, the stolen collective farm herd was returned to the village. The drovers said that somewhere near Kharkiv they were captured by the Germans and ordered to drive the herd back. Vasily Trofimovich Yatsyna was shot dead by the Germans in the spring of 1942 as an activist for the Soviet government.

The Germans drove this herd, like many cattle from the private sector, behind the Dnieper during the retreat.

Author: Yatsyna Viktor Petrovich

Notes, memories, reflections on the fate of my homeland – p. Krivushi.