In March 2014, soon after the annexation of Crimea and the referendum held there, I called my cousin in Sevastopol on Skype, then my uncle. My brother and his wife were tipsy, happily waved Russian flags at me, and told me that everyone around was celebrating “the return of Crimea home.” But my 85-year-old uncle did not look happy at all. I asked him why he was so sad.

Because it could have very bad consequences.

What could be the consequences?

(In response, I was met with silence and a piercing gaze)

Well, it’s not a war, after all?!

(And again, silence at first. And then he changed the subject).

At that time, I did not understand what had happened. In addition to my brother, my friends lived in Crimea, and they were also delighted with what had happened. I sincerely believed that people had made their free choice. And I did not delve into the situation. Understanding began to come later, somewhere after a year. Uncle Vova and I never returned to this topic. He passed away in 2018.

I will remember our conversation for the rest of my life. The older I get, the more often I think about it. Those who are younger always consider themselves smarter than old people. Until a certain time. Until those who are even younger and “even smarter” start to step on their heels. In reality, the 85-year-old “Soviet” old man turned out to be smarter and more insightful than me. A modern woman, 36 years younger than him.

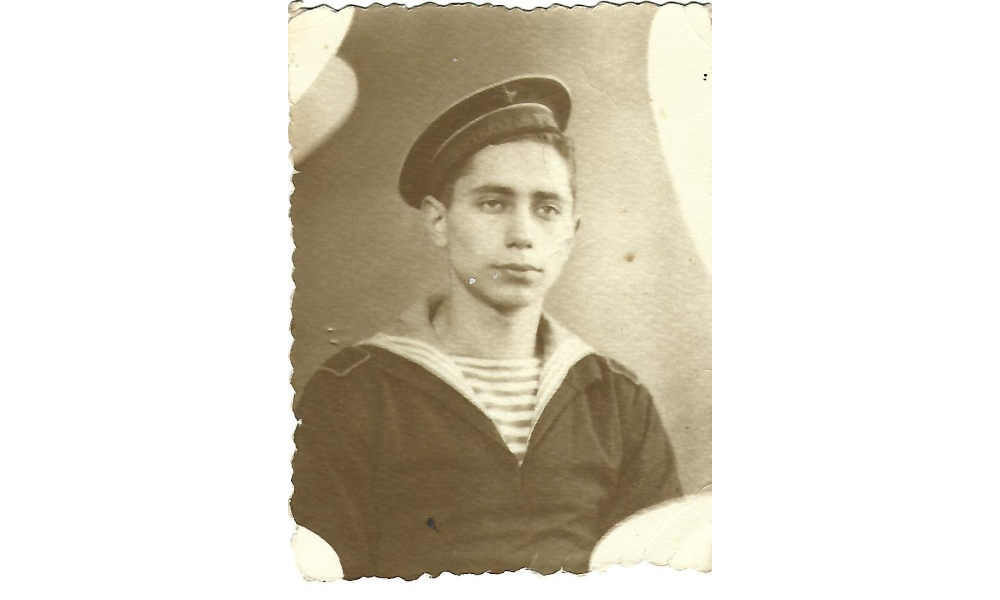

He was an extraordinary, worthy and very warm person. He lived a long, interesting life. He was an intelligent, educated naval officer, a captain of the second rank with two higher educations. I loved him very much, and he influenced me greatly and taught me a lot. My uncle, Vladimir Samuilovich Gertsberg, was born on February 16, 1929, in Kremenchug. A few years before the war, the family moved to Odessa, but never lost touch with Kremenchug. They would come to their hometown every summer. In 1941, the Gertsbergs arrived at the end of May. My grandfather was unexpectedly called up for several months to serve in the army for “retraining of junior officers.” And my grandmother went to her hometown with the children. After June 22, my grandfather managed to send his family in Kremenchug warm clothes, a certificate stating that he was an officer in the Red Army. And a letter with an order to urgently evacuate. Soon he died defending Odessa. So, at the age of 12, Vova became the only man in the family for many years. Apart from him, there were only women in the family. His mother, a three-year-old sister, grandmother, and Aunt Fanya, his mother’s sister, who was sick and could barely move. The military registration and enlistment office allocated them a cart for evacuation. Since none of them could handle a horse, they had to ask a neighbor. He seated his family, packed his belongings, leaving only 2 seats for them. Only Vova’s little sister and one woman could sit in the cart at all times. That is, an aunt or grandmother. And Vova and his mother with their things walked behind the cart all the way to Poltava. “It was very hard to walk. I don’t remember how we got there. But I will never forget the onion soup that they fed us at the station in Poltava. Fried onions and boiled potatoes. And I think I have never eaten tastier soup in my life!” Then there was evacuation to the Urals, to the city of Magnitogorsk. A barrack for evacuees. Mom went to work in a hospital as a nanny. She was the only breadwinner for the family. In 1944, he turned 15 and made the most important decision in his life. He learns that a naval preparatory school is being created in Leningrad, gets a referral from the Magnitogorsk military registration and enlistment office and goes to take exams. Let me remind you that the siege of Leningrad was lifted in January 1944. In the summer of 1944, the city was, in fact, a front-line city. The school primarily accepted students from naval schools that existed before the war, young men who had already been cabin boys in the fleet, sons of regiments. All of them were out of competition and accepted without exams. The remaining places were filled by young men based on the results of the entrance exams after passing a medical examination and sports standards. – Uncle Vova, how could you decide to do such a thing? And how did your mother let you go across the whole country alone?

I had no other choice. I really wanted to study further. From the 8th grade, schooling was then paid. And although the fees were not high, it would not have been easy for my mother. I would have to go and work at the machine. That’s what pushed me. I wasn’t going alone, but with a friend. Volodya Dymshits (Volodya’s father, Veniamin Dymshits, was then the head of the Magnitostroy trust, and later became deputy chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers]. The boy failed the medical examination and was not admitted to the exams.

And Vova Hertzberg went through all the tests. So, a fifteen-year-old Jewish boy from the city of Kremenchug, without anyone’s help, became a cadet of this unique school. The goal of the school was to educate the naval elite. It existed for only 4 years. Among its graduates were not only senior military officials, but also prominent scientists. The writer Valentin Pikul also graduated from it. Highly educated, experienced teachers taught here. In addition to general education subjects, they were taught music, singing, choreography, and rules of good manners. They had an excellent library and a good gym at their disposal. At the same time, the cadets served, went out Were on training ships at sea. Once they even had to accept a fight. Uncle Vova never talked about it. I just pestered him with the question of where he got the scar on his nose. He denied it for a long time and joked, and then told me that the cadets went to sea and unexpectedly had to take part in a fight. “I wasn’t supposed to be on deck, but I went up to look. That’s what I got for my curiosity.” He generally didn’t like to talk about the war, although he marched in a column of veterans every year. I thought: “What kind of veteran is he? He was 15 years old then. And when I was looking for information about my grandfather who went missing in action in the archives, I accidentally found a record of my uncle and his award during the war. He didn’t tell me anything on purpose. But I really loved talking to him about different topics and pestering him with questions. I remember a group photo of first-year cadets in 1944. Everyone’s faces were terribly thin from malnutrition. As a teenager, I learned from him that not everyone in besieged Leningrad was starving. In 1944, there was still hunger. One time, a fellow cadet took him to work to see his mother to feed him. They went down some steps, apparently to a restaurant that was not open to everyone. There was a huge variety of food there. And Vova fainted, lost consciousness from the smells and what he saw.

Once I read on the Internet that among the cadets was the son of the then People’s Commissar of Finance of the USSR (i.e. the Minister of Finance) Vladimir Z. He (supposedly) served on an equal basis with everyone else. I asked about it. “Yes, there was one. He was older than us, he was over 18 years old. They hid him from military service among us. He did not live in the barracks, but in a separate room. He also ate separately, they even brought him girls. It is not worth remembering him.” Vladimir Samuilovich graduated from a preparatory school and was assigned to the Baku Higher Naval School. He served in the Black Sea Fleet. He received another higher education in absentia – in economics. He retired with the rank of captain of the second rank (lieutenant colonel). Which was no small achievement for a Jew in the Soviet army. Then he worked for about 30 years at the Sevastopol rocket and artillery weapons repair plant, first as deputy head of economics, and before retirement as a quartermaster. He retired when he was already over 70 years old. My uncle was not an angel or a superhero. He was smart, cheerful, very sociable, and a person with a winning personality. He taught me a lot. Coming to Sevastopol every summer, I not only swam in the sea. He gave me books to read that he himself had read. Remember “samizdat”? Forbidden literature that was reprinted and passed from hand to hand? I also started reading the Bible with explanations for the first time during the summer holidays, when I was about 14. I could ask him everything that I was afraid to ask my parents. He taught me how to drink so as not to get drunk. How to fight back against an impudent person. And many other very important things. None of my friends in Kremenchuk had such an uncle. I remember him with pride, love and gratitude. Especially today, 80 years after the end of World War II, when my cousin in Sevastopol is waiting for Putin’s “victory parade” tomorrow. His father would not have done this. He was wiser, he survived that war.

Author: Irina Barsukova